The Issue with Cheap Stocks

Why buying ‘cheap’ stocks can backfire—and what to look for instead.

As value investors, we try to buy companies for less than they are worth. Sounds relatively easy, right? Well, it's not. The reason is that, first, there are many ways to value a company. Is it cheap relative to its underlying assets? Is it cheap relative to its earnings? Is it cheap relative to the sum of its parts? Is it cheap relative to its sales? The second reason is that businesses are not static. Earnings fluctuate, they can go down or up. Assets can be bought or sold. This means that on a "static" basis, a company may look cheap by any measure. But in the stock market, you get paid not for the present value of a company, but for its future value.

And what does cheap really mean? Is a P/E of 15 cheap? Is a P/E of 10 always cheap? Should you only buy below book value?

I've looked at thousands of companies and read hundreds of pitches, so let's look at some real-world examples to try to answer these questions.

So cheap you can't believe it, but did it work?

In March 2023, I started a write-up with the following title: “FP Newspaper ($FP.V) - buying a shrinking business for 3x FCF”

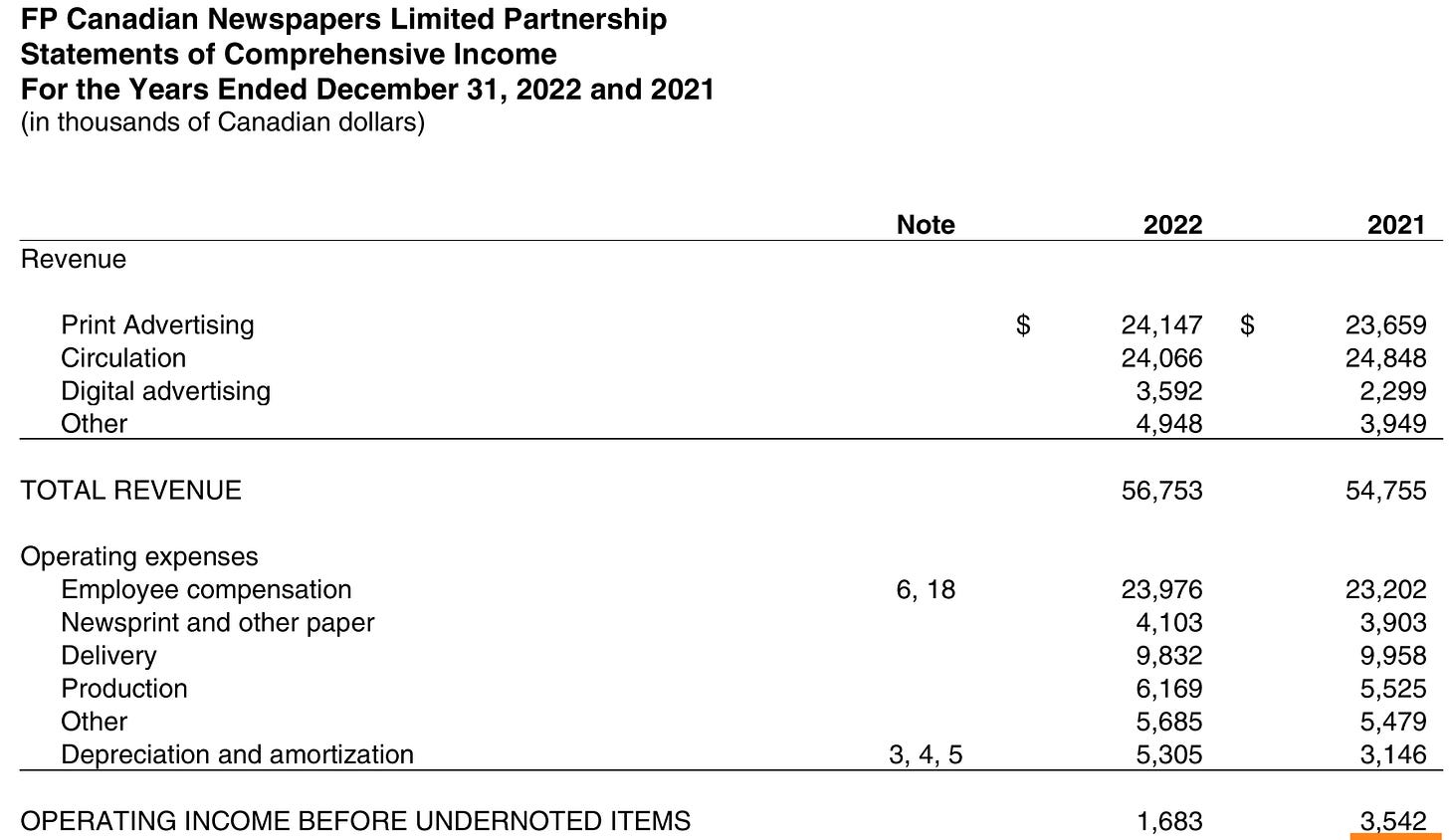

FP Newspaper owns securities representing 49% of the cash flow of FP Canadian Newspapers Limited Partnership ("FPLP"). FPLP owns the Winnipeg Free Press and other smaller regional news and media publications in print and digital formats. At that time, FP Newspaper's market capitalization was approximately CA$5.5 million. In 2021, the underlying business generated CA$3.5 million in EBIT. FP Newspaper is entitled to 49% of that, so that would be CA$1.75 million. Or 3x EBIT. Dirt cheap.

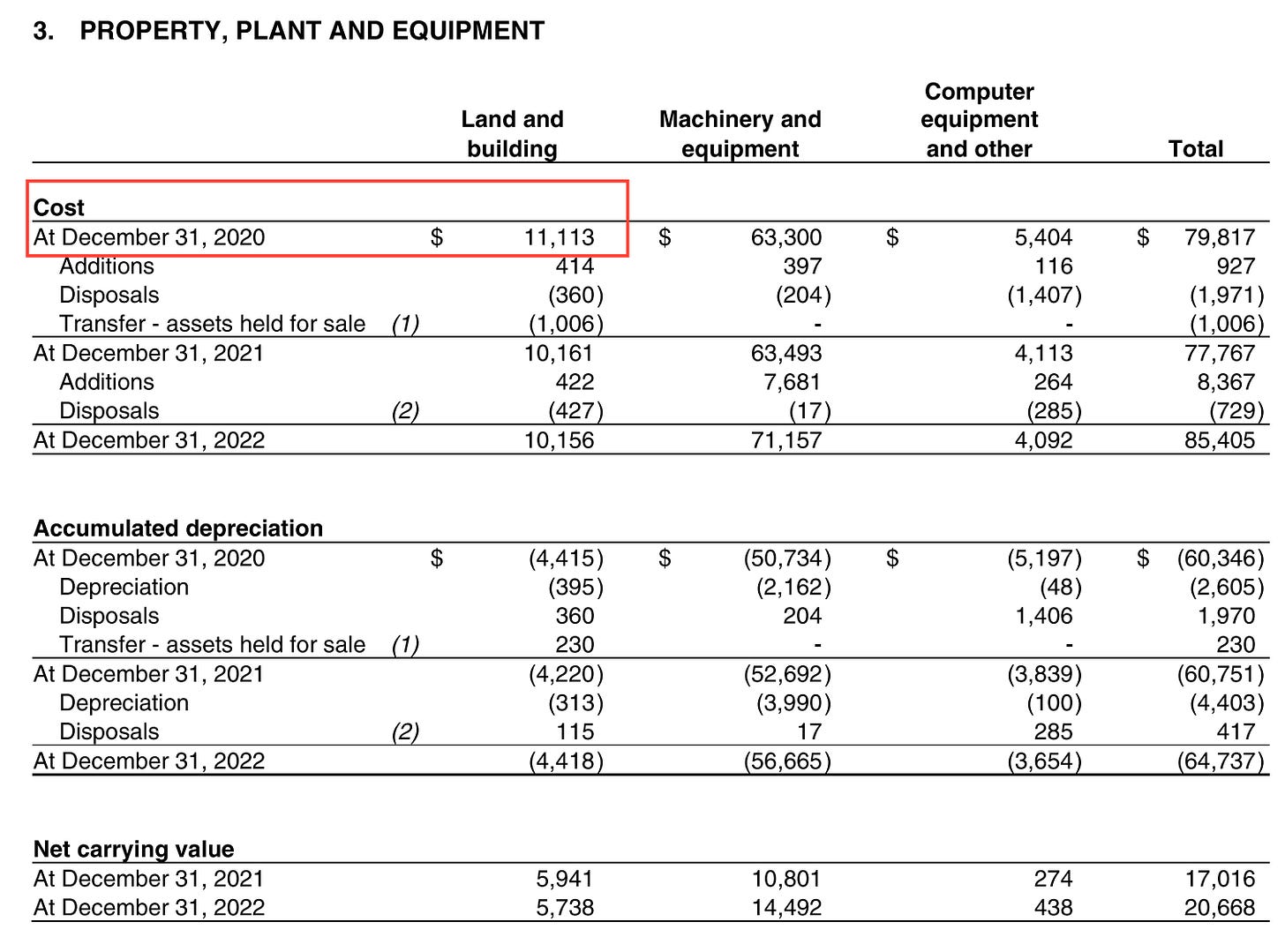

The company also owned real estate that was probably worth more than the market capitalization of FP Newspaper (on a 49% basis). See Land and buildings at cost.

So any way you slice it, the company was cheap. What would you expect, how did that work out? Buying a company at 3x EBIT, below liquidation value?

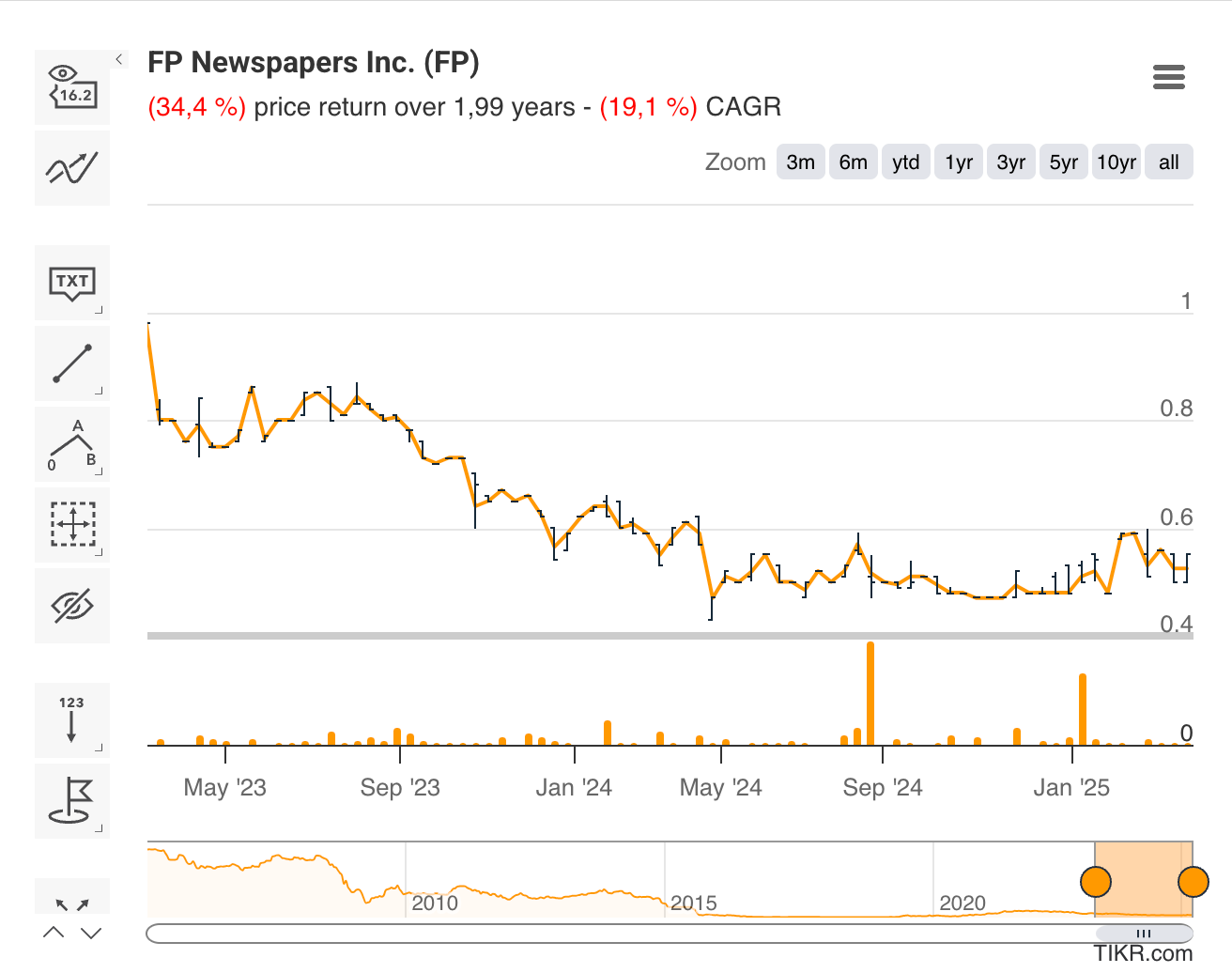

It worked out badly. The stock is down 34% since then.

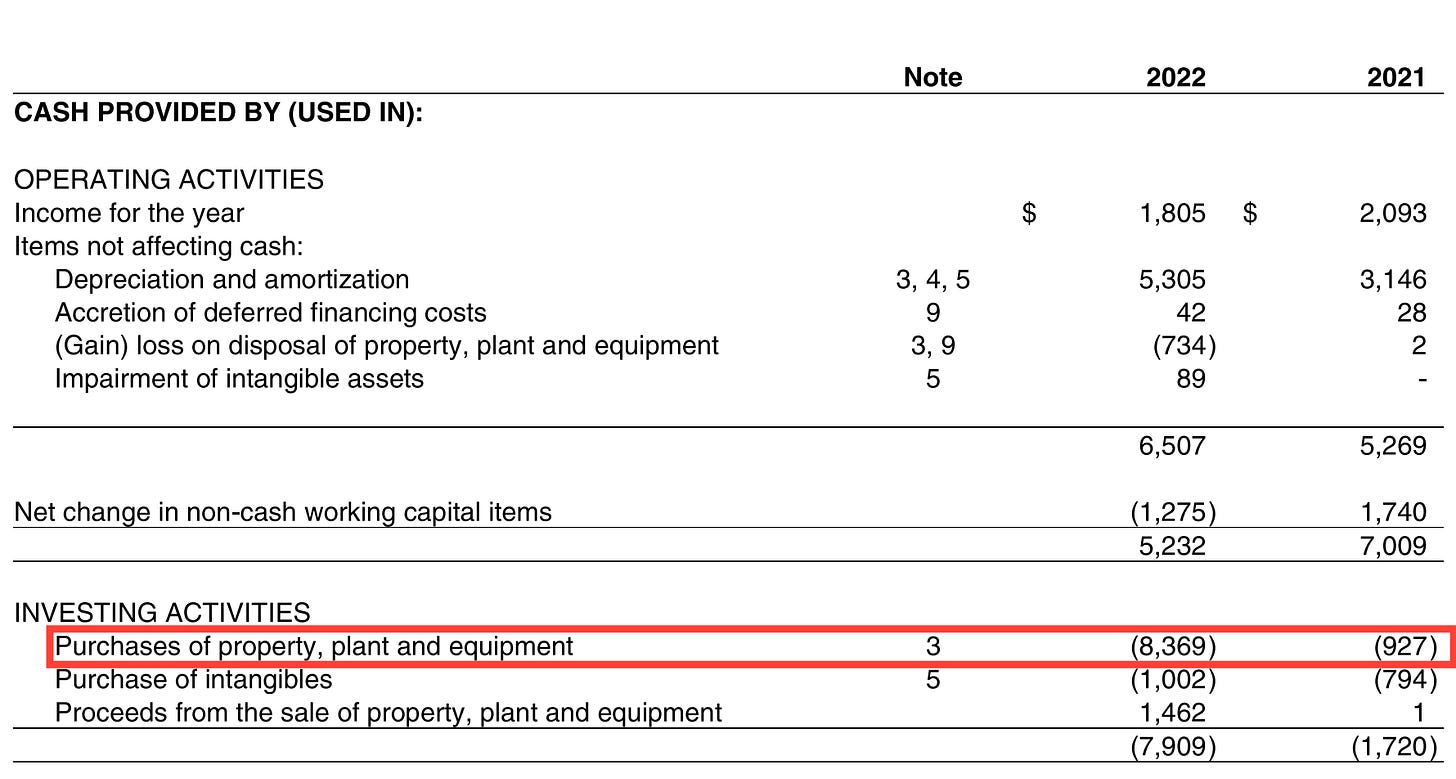

Now, what are the reasons for that. First, they bought a printing press for CA$10 million (see Purchases in PP&E) — only then to return it back.

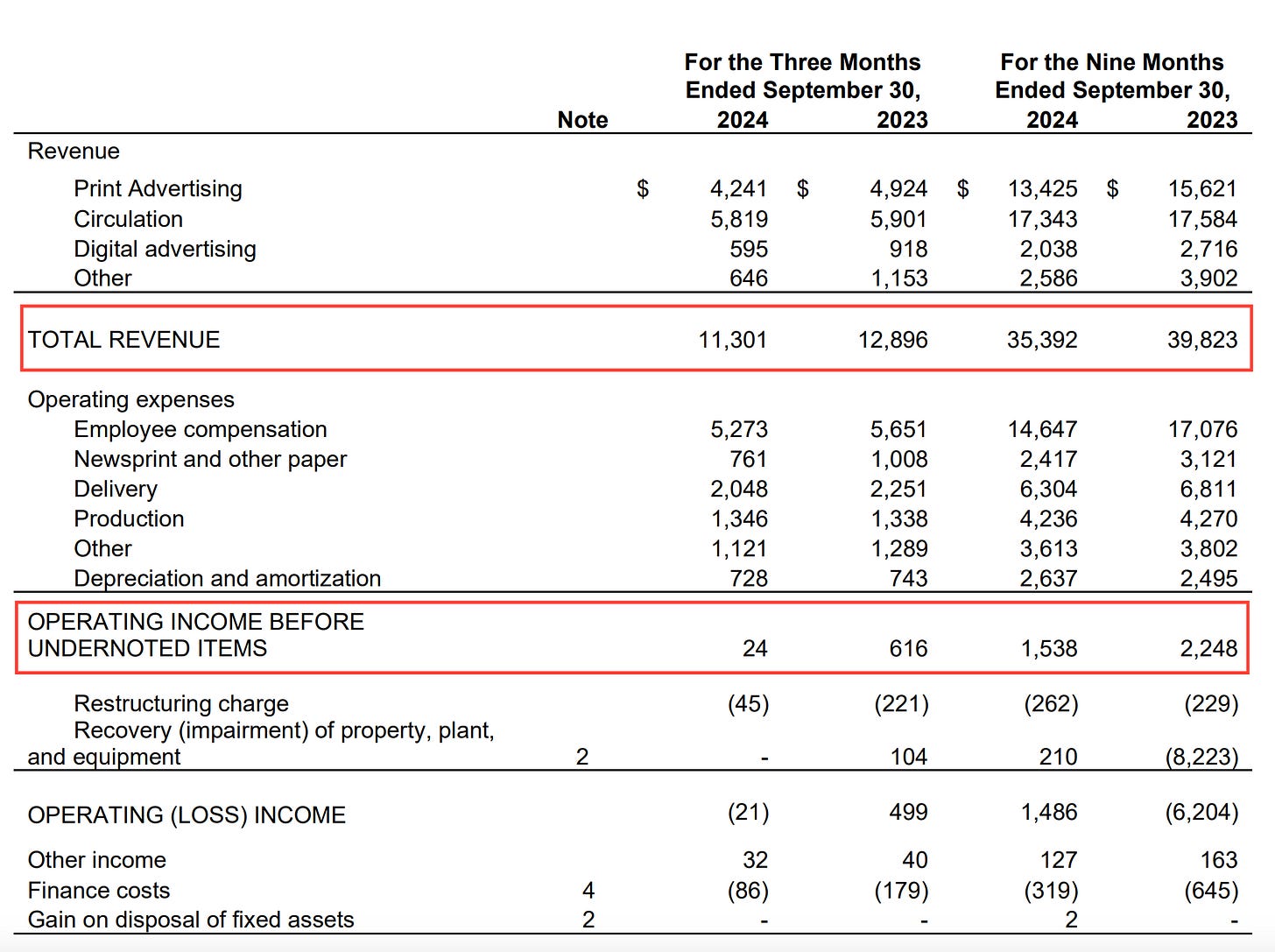

This was obviously a huge mess, destroyed capital and trust from the investors. On top of that. The reason the business was so cheap, is that it operates in a dying industry. Hence, the earnings have been declining ever since. I don't follow the company anymore, but let's just look at their most recent earnings:

Sales and earnings are declining. The stock used to trade at 3x EBIT. It still trades at 3x EBIT even though it has lost 34% of its market cap. This is not the only example, another stock I looked at briefly is Yellow Pages.

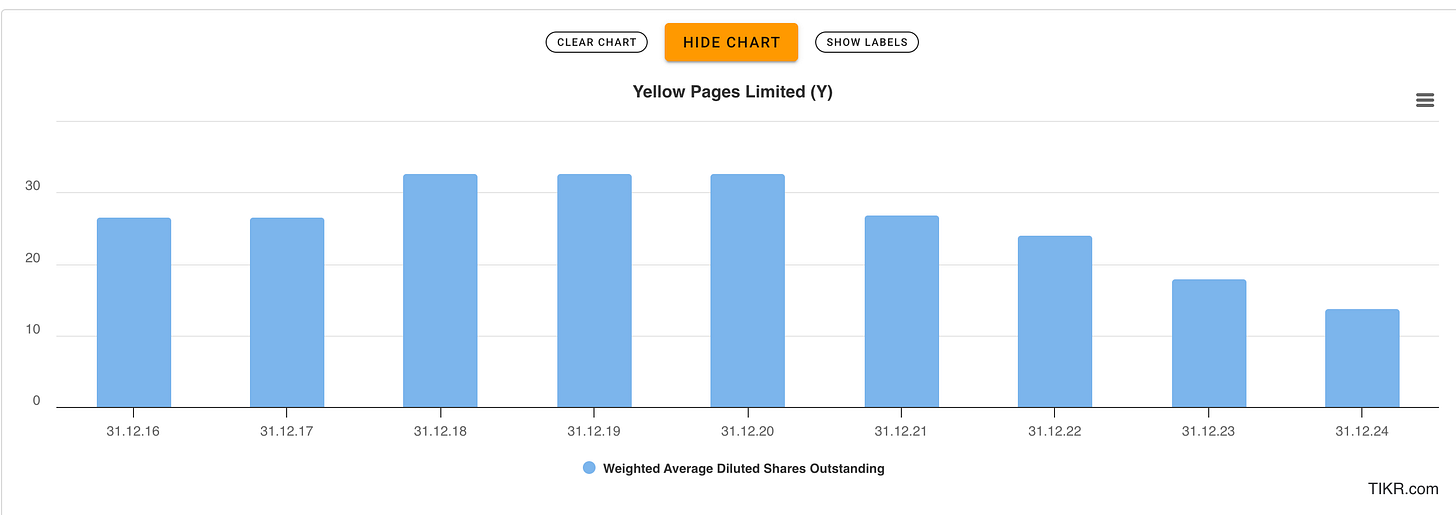

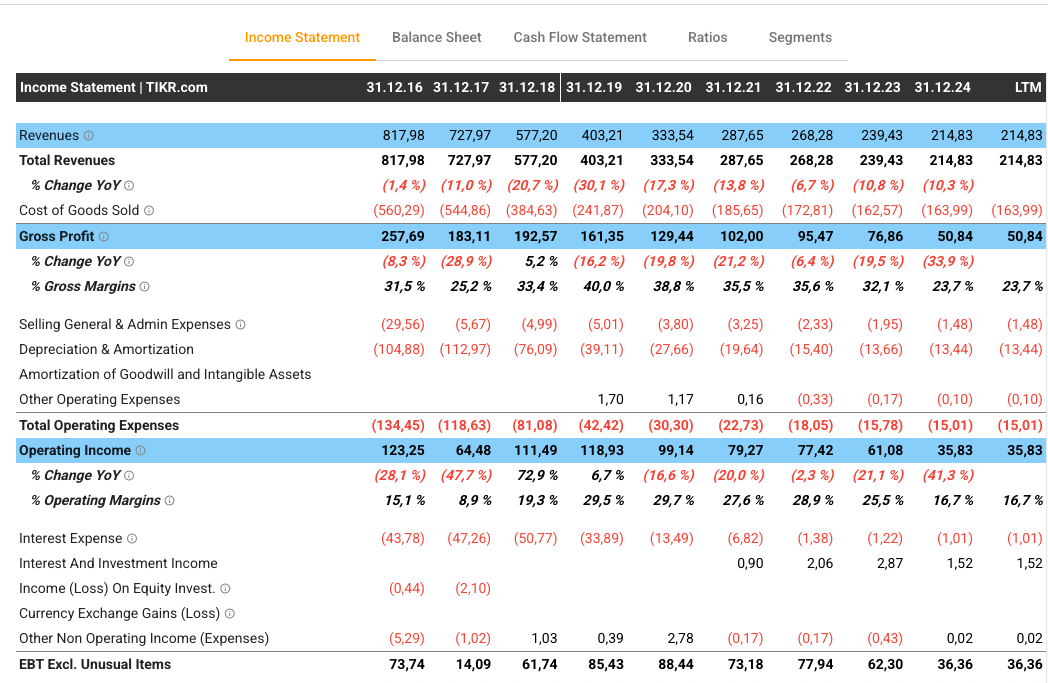

In 2022, the company was trading at an EV of about CA$250 million. Their EBIT in 2022? $77m. Again, 3x EV/EBIT. And they were buying back shares. It doesn't get any better than that. Just look at the number of shares outstanding:

A value investor’s dream! Now let’s look at the share price since then:

Now, to be fair, they have returned CA$2.45 per share in dividends over that period, so including dividends you are almost breaking even. But still far away from being a home run investment. Despite the cheap valuation!

The reason? While the operating income stood at CA$77 million in 2022, it got sliced in half since then, EBIT in 2024: CA$35 million!

It looks expansive, how should that work?

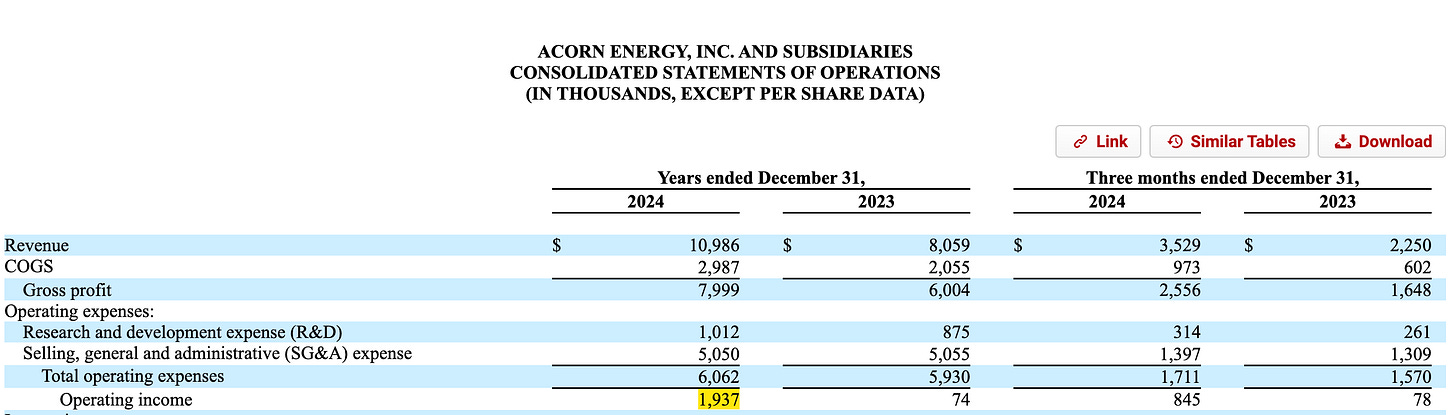

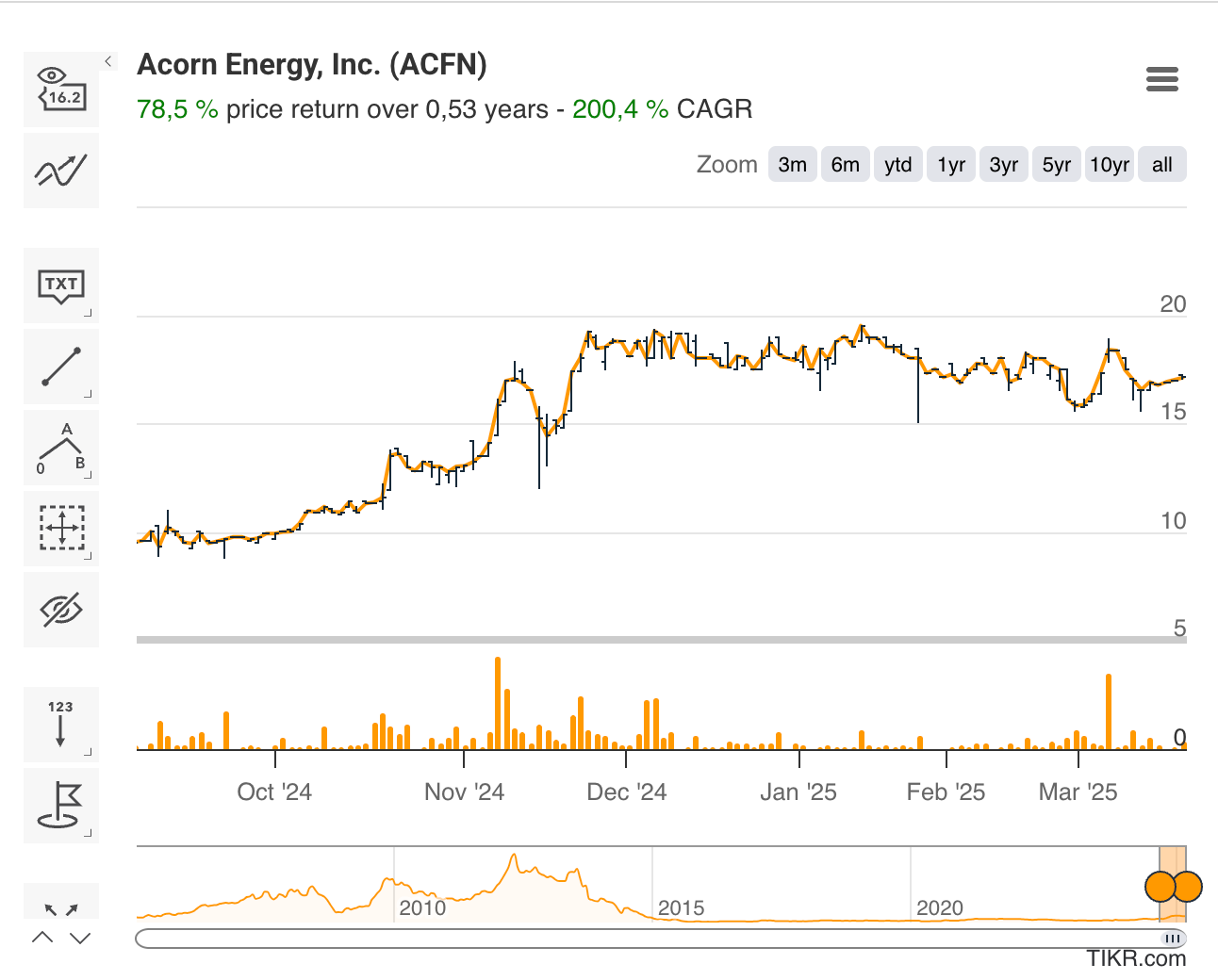

In September last year, someone pitched me Acorn Energy (ACFN). The stock was sitting at an EV of $22 million at that time. LTM EBIT was $0.43 million. Meaning 51x LTM EV/EBIT. For comparison, Google currently has a LTM P/E of 20. Should a Microcap trade a premium to Google? Probably not, but ACFN has also just announced a new $5 million contract. So you could see an increase in earnings in the following quarters.

And it did increase, in the next two quarters the company earned $1.61 million.

The stock since September? + 75%.

Is the stock cheap now? At 22x EV/EBIT (LTM) probably not, but it is cheaper than it was in September based on LTM numbers. I do not know the business well enough to predict its future earnings power. I do know it is a good business and probably deserves a premium - and after all, what counts is what they earn in the next two years, not what they earned last year.

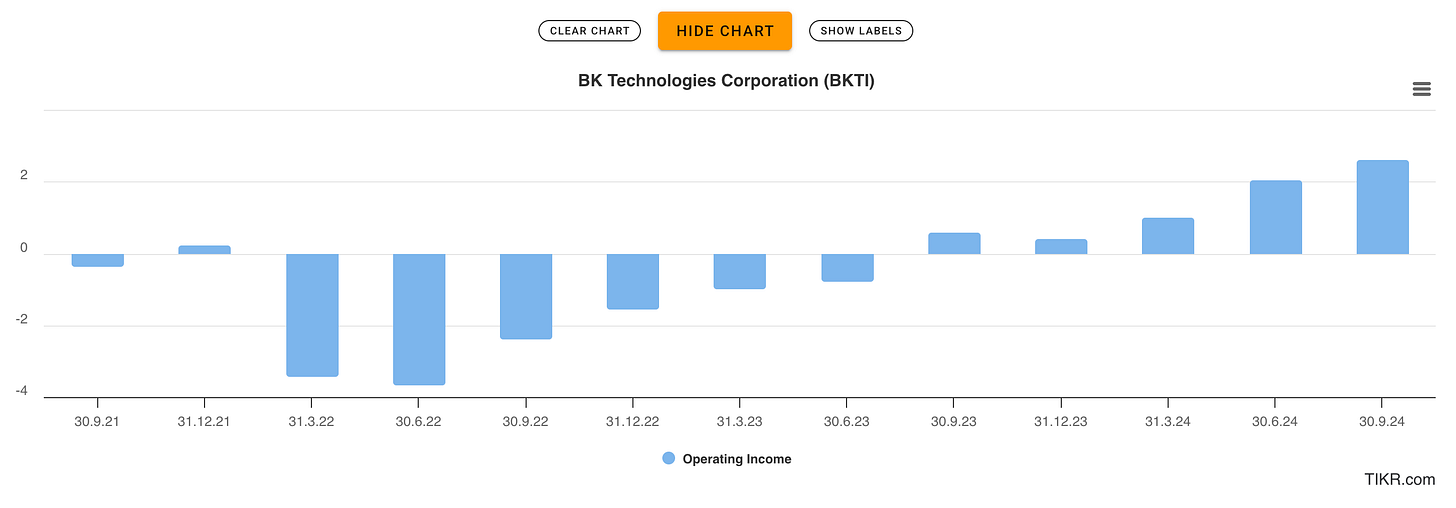

In May 2024, I wrote about BK Technologies, BKTI. A $40 million market cap company at the time. The company just became profitable in the last two quarters of 2023. In Q4 of 2024, they did $0.40 million in EBIT. Annualized to $1.60 million and the stock would have traded at 25x EV/EBIT. Not super cheap and first glance, plus I was skeptical that they could continue to grow earnings that much going forward.

It turns out they could.

The stock is now valued at $40 million anymore, but at $100 million.

I could go on with examples for both type of stocks. Stocks that seem screamingly cheap, but will always stay cheap. And therefore never perform. And stocks that seem expansive in the rearview but cheap(er) going forward, and therefore have performed.

Verdict

My biggest winners and my biggest errors of omission have one thing in common: They were both undiscovered companies that grew their earnings. As investors, we sometimes get so focused on what's in front of us NOW that we don't focus on what could be in front of us 1 or 2 years from now. There are two components to valuing a company. Price and earnings. If you are “sure” (as sure as you can be) that earnings will increase, then you know that the company will look at least optically cheaper in the future than it does now. The market is likely to re-rate the company and therefore increase its price. The best way to avoid a value trap is to buy a company that is growing its earnings.

I agree that undiscovered companies that grow their earnings is the best, even better if they are at an inflection point between break even and profitability. Harder said than done, as it requires a lot of digging.

Pure cheapness works better in a basket type of approach, then statistically some rerate or provide good capital returns, while others stagnate, with no investor interest. But sometimes investor interest comes back without even improvements to the business (Alibaba, BATS).

If you want to buy super cheap stuff you need two things.

The first is a DCF which shows it is significantly undervalued, and in which you have reasonable confidence (often you don’t need to physically do the DCF, because it’s obvious and you’re decent enough at maths to know broadly what the DCF would tell you. But you need to understand the idea. Eg a company whose earnings will drop 10% per year at 5x earnings is not cheap, it’s about fair)

The second is management that understand their situation and are dedicated to maximising shareholder returns. Most of the time, this means ploughing cash into buybacks, rather than trying to dig their way out with a big expensive capital investment.