The Sweet Illusion of Insider Ownership and What Really Matters

Looking Beyond the Sugar to Discover the True Ingredients of Successful Returns

I have always been fascinated by the topic of correlation vs. causation. Simply because it is extremely difficult for us humans to distinguish between the two. It takes a lot of thinking to be able to distinguish between the two.

I‘ll give you an example.

I would bet that 80% of people would agree with the statement that sugar makes you gain weight. But that's not true. However, there is a correlation between eating sugar and gaining weight. Sugar is nothing more than a carbohydrate. 1 gram of carbohydrate has 4kcal. But since sugar is already processed, your body has no work to do in processing the sugar. As a result, your blood sugar rises, which makes you hungry, which makes you likely to eat more, which can lead to an excess of calories, which makes you fat. You see, sugar itself is not the cause of weight gain. It is the excess calories that make you gain weight.

So I asked myself, what is the sugar of investing. Something that is a widely held belief that it matters, but it really does not matter.

Insider ownership, the sugar of investing?

”We want every management team we are invested in to pay themselves a small salary, own 30% of the company and buy stock every quarter. But in reality it is much more nuanced than that.” - Ian Cassel

Every investor likes management with skin in the game. The explanation is easy: “show me the incentives and I show you the outcome.” - as once the late Charlie Munger said.

But does it really matter?

The data says otherwise.

The same also suggests this study:

The same goes for insider selling. Usually perceived as a bad signal from the market. When insiders sell, there must be something wrong with the company's future prospects. But the reality is different. In most 10-baggers, insider ownership has declined over time. Check out this story from Monster Beverage, where insiders sold just before the company had its breakthrough with their Energy drink segment.

And this is no exception, but rather the rule:

If I wanted to find a reason for this, I could imagine that a lot of family-owned companies have high insider ownership - and are probably a drag on the returns of the group with high insider ownership.

As with insider selling, a lot of stocks that have gone up a lot attract insiders to finally realize their gains.

But the truth is that what matters is management performance. Management performance is hard to predict, so we look for potential indicators to predict their behavior. The truth is that these indicators are much more nuanced than we would like them to be.

If management ownership is the sugar, what is the caloric deficit in investing?

The issue is that investing, unlike dieting, is as much art as it is science.

Essentially, we try to predict the future of any given company. We look for clues to do so. Some might be useful, other less. Sometimes, we fall in love with certain clues, that are maybe just noise, and not signal. So it is important to take a step back and ask ourselves.

What are we trying to achieve?

Well, if you are reading this blog, probably the highest possible IRR with the lowest possible risk.

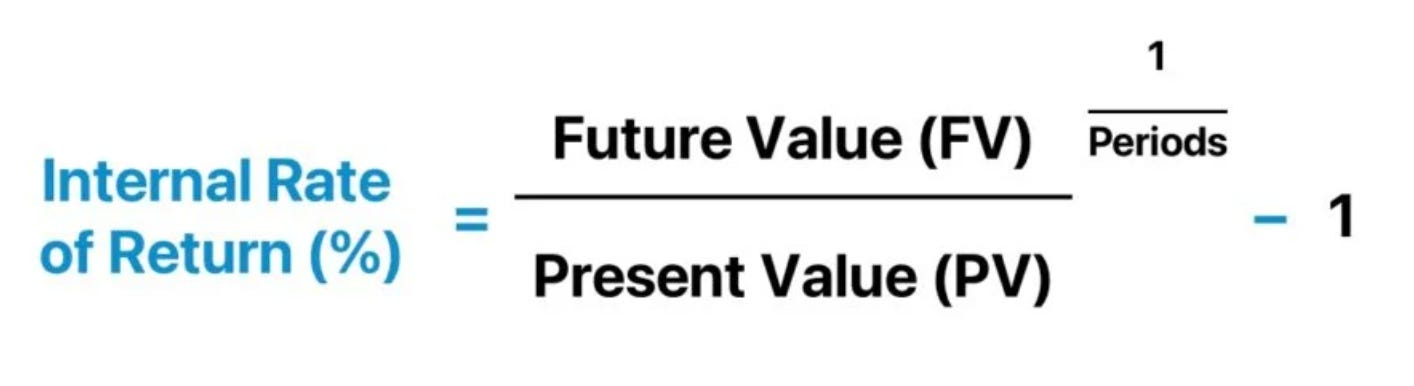

So, from a first-principles perspective, we should first figure out what IRR is and how it is calculated:

We have three parts, that make up the equation. The future value of a company, the present value and the time (periods).

How can you achieve a great IRR?

I don't pretend to be able to predict that. But I do think there are some things that will increase the odds of getting a great IRR.

Chose your hurdle rate

Take dieting again as an example. First you need to figure out how much weight you want to lose (or gain), and from there you can calculate your calorie deficit to reach your goal. Ultimately, you could break it down into specific meals you should eat to reach your caloric deficit on any given day.

Investing is hard. We cannot predict exactly how much IRR a stock will generate. But I believe we should ask ourselves what IRR do I want to achieve. There is no guarantee that you will achieve it, but it will dictate the stocks you look at.

For a long time, I just bought stocks without knowing if they were even capable of delivering the returns I wanted. This was often dismissed as "just a temporary underperformance". Until one day when I sat down and went through every stock and asked myself: "Can this stock even give me an IRR of 25%+?”

For most, the answer was no. It was not a temporary underperformance, it was structural. Maybe your hurdle rate is 10%, maybe 20%, maybe 30%, whatever it is, I would add a margin of safety. Your betting average is not going to be 100%. So even if you want to compound at 20%, I would aim for at least 30% IRR on any single stock because you are going to get things wrong.

Trying to estimate the IRR for your investment

We can make money in a stock in three ways:

- Multiple re-rating

- EPS growth (by earnings growth or buybacks)

- Dividends

So you can look for companies trading at 4x earnings that you think are worth 8x earnings. 100% upside. If it takes the market two years to close the gap, you've had a 41% IRR.

You can look for companies that you think could potentially double their EPS over the next two years. With no multiple re-rating, you'd get 100% upside, or a 41% IRR.

You could also look for companies that want to liquidate but are trading 20% below liquidation value. If the liquidation happens within the next six months, you'd have a 40% IRR.

This is the beauty of investing, the art part. There is no one way to make money. There are many ways to skin the cat. You have to find what works for you.

Probabilities and uncertainties

In our spreadsheets, every investment case had a great return. Every investment case worked. But in reality, that is not the case. We are dealing with uncertainty. If there was 100% certainty, the opportunity would not exist. So when you calculate the potential IRR, you should add a potential certainty to those results. What could go wrong? What is the worst-case scenario? And would you be comfortable with that?

Personally, I think about this in two ways.

Prevention and assessment.

A little metaphor: If you want to lose weight, prevention would be not having any unhealthy, high-calorie food in your house. If you don't trade on margin, if you avoid highly leveraged companies that have a real risk of going bankrupt, if you don't go all in on a single stock. You can avoid a lot of bad things.

The assessment would be to know when you can eat something unhealthy because you are still in caloric deficit. In investing, your judgment would be that you come to the conclusion that you can trust management, that your earnings forecast is correct, and that the potential multiple you estimate is reasonable. This is the hardest part.

Closing thoughts

The truth is, that even we as investor are not rational people. We try to act as rational as possible, but are still emotional human. Maybe insider ownership does not matter, maybe a lot of other clues we look for do not matter. At the end, what matters is the difference between the current and the future value of a company.

But sometimes it helps to follow non-logical strategies, if they help us to sleep well at night. If they give us a compass to follow, if we want them to matter, they will matter.

I want to close this article with one last metaphor. There are still many people who follow diets that from a first principle standpoint do not make sense. They avoid calories at night, or do fasting in the morning. A lot of these people achieve their goals, but not because they fasted or did not eat anything at night, but because of the caloric deficit that was achieved by this.

The same goes for investing, your results were not achieved because the stock had 30% ownership, but because the companies future value was higher than the value you bought it for. But the 30% ownership may be important to you. It lets you sleep well at night. And that is what matters, that it works for you.

Great piece.

I am not surprised by the finding that insider activity is not a good indicator of subsequent shareholder returns.

Remember that insiders have a very narrow field of vision. They know about their company and their industry, but they have no peripheral vision in relation to anything else. They live and breath their business - its all they know.

Investors like you and me are very different. They analyze different companies, in various industries and across diverse geographies. They have a wide field of vision and far better perspective. So when an investor decides to buy or sell shares in a company, it is generally a determination based on opportunity cost and the ability to move money freely from one business to another.

In contrast, when an insider decides to buy or sell, it is rarely based on opportunity cost. Sales are often influenced by the need to settle tax liabilities or personal expenditures (perhaps sending the kids to University) and often have nothing to do with the future prospects of the company. Buys are often influenced by recent price action because very few corporate executives understand how to properly value a company or its shares. Instead they think to themselves, "the share price is 20% lower than where it was earlier this year, I can buy now and catch the bounce".

The only time that insider influenced buying is a good indicator is when you have a savvy CEO who understands markets, only repurchases shares when below intrinsic value, and goes on a buying spree. Berkshire Hathaway is the best example.

Most stock buy-backs occur well above intrinsic value, regardless of the share price, simply to offset dilution from SBC. In these circumstances, they are not a good indicator for external investors.

I think you're pointing to an important lesson: Investing is messy because trying to predict the future is a soup consisting of a ton of ingredients. In a delicious soup it's hard to say exactly what ingredient is the root cause for the deliciousness.

But I think you're taking it a bit to far to say the many pieces leading to higher value is not the cause of the higher value.

In a delicious soup, it would not be wrong to say that the chicken broth is the cause of the great taste, but so was the carrot, the thyme and also the water.

What I'm trying to point at is that (as you rightly point to) there's a bunch of stuff that is the cause of higher future value. And I think that done right, inside ownership is one of those contributing to a higher future value. But it is not a guarantee against mismanagement (nobody wants to fail at their job).

Thank you for a thought-provoking piece 🙌