How a “High-Probability Insight” Resulted in Buffett’s Best Investment…

…and what we can learn from it

In 1963, Warren Buffett did something unusual for a value investor—he sat in Omaha restaurants, watching people pay their bills. He wasn’t there for the food. He was there to see if customers still used their American Express credit cards after one of the biggest corporate scandals of the decade.

That fieldwork turned into a 40% position in his partnership and would account for one third of its profits in the following years1. It marked the most successful investment for him during that time. I think it offers great lessons for every investor to learn from.

The Asset-Light Compounder

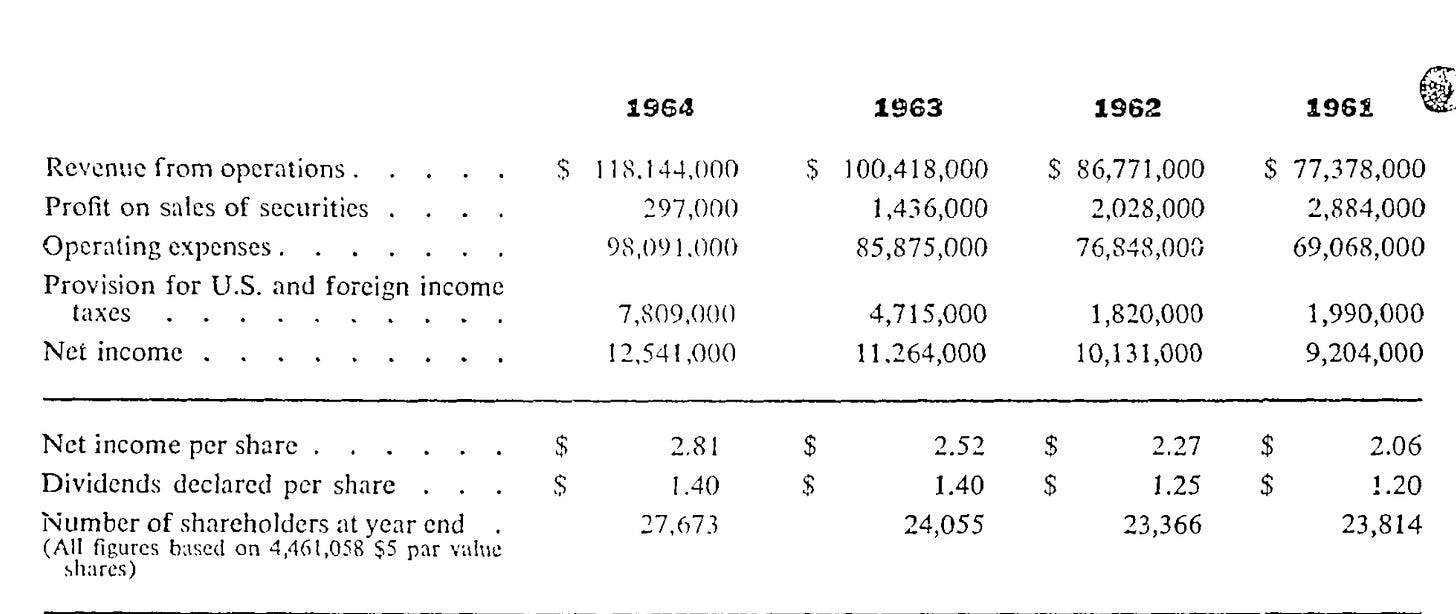

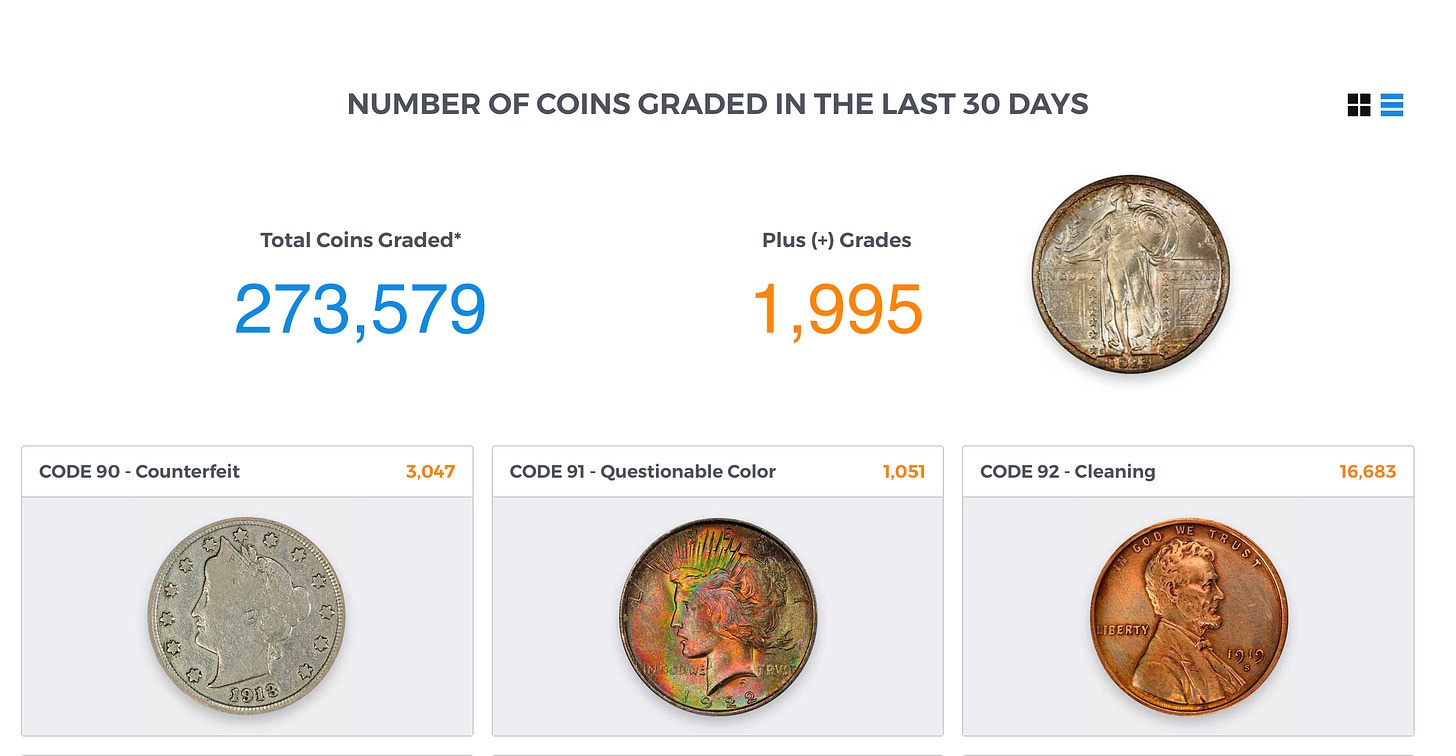

American Express was special. This was a high-quality business. Asset-light, growing with clear barriers to entry and a brand name that enjoyed a great reputation. On top of that, during this period they had just started earning a profit from their new credit cards, hence the business also had an inflecting segment, that would be another tailwind for its growing earnings.

However, American Express was not an obscure microcap at this time. It was a well known company. For comparison, the market cap American Express had during that time in % to the largest company, would equal a $20 billion market cap company today.

These companies are usually never cheap, and even Buffett paid a relatively high earnings multiple of 15x.

The Scandal

In 1963, American Express had a subsidiary that offered warehouse receipts. It was a tiny part compared to the rest of the business. In most years the subsidiary even lost money—and in the year it did make money it was merely 0.11% of American Express’s overall net profit2.

De Angelis, a soybean oil trader, stored oil in containers to use them as to use them as collateral to borrow money from banks. American Express would issue the receipts confirming the amount of oil in the tanks, so de Angelis could use them as collateral. The issue: de Angelis was running a scam, in which he overstated the amount of oil in the tanks and filled them largely with seawater, placing oil only at the place where inspectors would check.

De Angelis saw his opportunity to borrow more money to buy $1.2 billion pounds of soybean oil.

When the soybean oil price eventually collapsed, his lenders went to American Express, with their receipts of De Angelis collateral. Only to find that there were almost no oil in the tanks.

The scandal was all over the news. American Express was liable for roughly $120 million in claims. American Express shares fell from $62 to $35 at the lowest point.

Investors were even questioning whether they could be made liable for the claims. But, more importantly, the question was whether it had lost the trust of the consumers.

The Investigation

Buffett went to restaurants in Omaha, to sit there and see if people would still use their American Express credit cards and traveler’s cheques. His friend Henry Brandt, who was Buffett’s full-time sleuth, spent weeks interviewing bank officers, hotels, restaurants how American Express was doing and if the use of their products had dropped off.

Eventually, Buffett came to the conclusion it had not lost the consumer’s trust and the main business of American Express was unaffected. On top of that, it became clear that the overall liability of American Express would be no more than $40.6 million—by contrast, the market cap at this time was $178 million and American Express had a net cash position of roughly $50 million, earning close to $12 million in net income, growing double digits.

First, he bought 70,000 shares at roughly $40 a share, or 1.6% of the company. Over the next two years, when American Express business was firing on all cylinders, he kept buying until he owned 5% of the company3.

American Express eventually made up 40% of his partnership. In dollar amounts, it was his best investment. Shares quadrupled from his initial purchase price of $40 to more than $160 a share, four years later4.

In his 1967 letters, he concluded:

“Interestingly enough, although I consider myself to be primarily in the quantitative school (and as I write this no one has come back from recess - I may be the only one left in the class), the really sensational ideas I have had over the years have been heavily weighted toward the qualitative side where I have had a ‘high-probability insight’. This is what causes the cash register to really sing. However, it is an infrequent occurrence, as insights usually are, and, of course, no insight is required on the quantitative side - the figures should hit you over the head with a baseball bat.5”

This investment also marked his change in strategy from buying quantitative cheap assets to conducting a qualitative analysis. For me, there are three important learnings we can take from this.

Lesson #1: Quality + Temporary Crisis = Opportunity

His timing was important. He bought a high-quality, growing business when its shares plummeted by over 30% due to a temporary problem that would not affect its earnings going forward.

Would he have bought American Express before the scandal at $60 a share, and his returns would have been roughly half of what they were.

Usually when an individual stock plummets that much, there is a reason, and obviously there was a reason here as well. The critical piece is determining whether this problem is really temporary or permanent damage to its brand.

Lesson #2: What’s your edge

And this exactly is the most essential part. The critical piece is the work Buffett did, that others were not willing to do, to determine whether this problem was really temporary or permanent damage to its brand.

He called it a “high-probability” insight. He gained it by not just reading 10-Ks at his desk in Omaha, but by doing scuttlebutt in person. Going the extra mile.

What This Looks Like Today

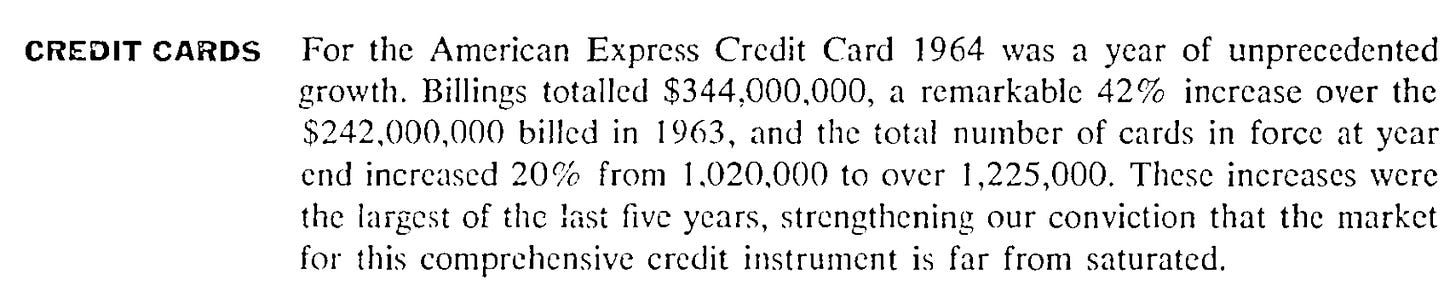

You don’t need to sit in restaurants and sleuth how many people still use their Amex or interview hotels about it. Buffett did not have internet back then, now we have access to it. Sometimes you can use differentiated data to predict the next quarter, like Dirtcheapstocks did with Four Corners:

Four Corners was a publicly traded company that sells bingo-supplies/equipment. The company is no longer public.

The company would file their revenue with the Texas state before they would file their quarterly results. Even though this information is public, not a lot of people would even follow the stock, even less would conduct this research.

Dirtcheapstocks, however did.

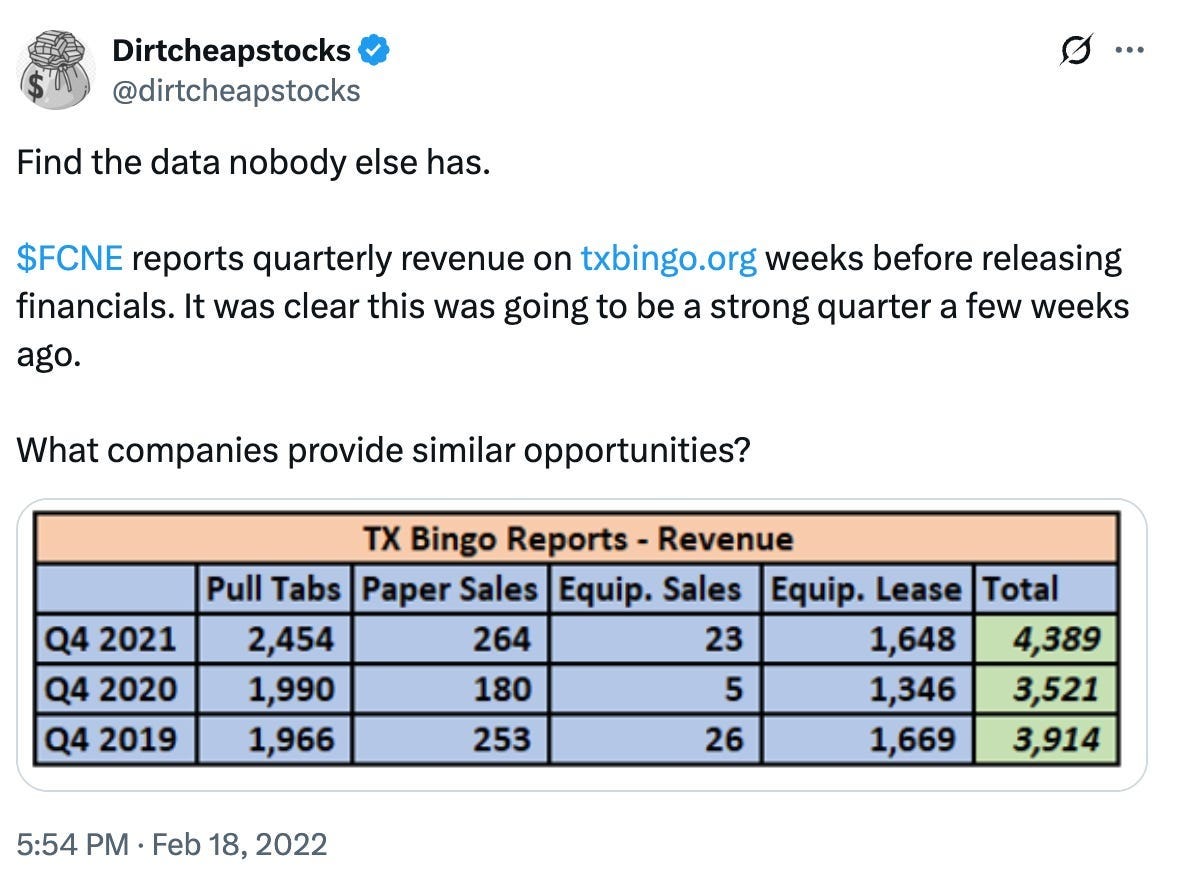

Another example was Collectors Universe in 2021. Collectors Universe was involved in grading and related services for collectibles. The company is also no longer public.

Harris Perlman described, in a podcast with Planet MicroCap, that he found a website that would state how many coins were graded in the last 30 days.

This provided him with an edge over other investors, which most of them have likely not used this data.

Just as Buffett visited restaurants in 1963, today’s investors are conducting research to come up with alternative data sets. The medium has changed, but the principle hasn’t.

Lesson #3: Probabilities Should Drive Position Size

Two things stood out to me here: First, yes, when you have a “high probability” insight, you should bet big. However, it is important to be honest with you—the odds that you find a high-quality, growing company with a temporary problem that you conclude with facts is indeed temporary, is very, very low. In most cases, either the company is not high-quality or you don’t really have an edge.

The next thing that stood out is that he likely averaged up as American Express earnings increased, and the scandal was getting resolved. He started with 1.6% of the company and eventually owned 5%, letting it grow to 40% of his partnership. American Express accounted for a third of his overall partnership gains during 1964-19676.

Closing thoughts

Investing is a game of probabilities. We want to make sure the probability is high that we are right, and the person who sells shares is wrong. There are multiple ways to define what having an edge could mean: such as having a longer time frame as the seller, but I think the most reliable one is to have a “high probability” insight. This can come from many sources, real life sleuthing, alternative data sets, talking to other investors, competitors or management. But you have to look for it first, in order to find it.

Brett Gardner, Buffett‘s early investments

Brett Gardner, Buffett‘s early investments

Alice Schroeder, The snowball

Brett Gardner, Buffett‘s early investments

https://www.safalniveshak.com/wp-content/uploads/2013/12/Warren-Buffett-Berkshire-Letters-1957-2012.pdf?

Brett Gardner, Buffett‘s early investments

Best yet is doing a little dumpster diving. Unbelievable amount of information can be gleaned, just wear gloves.

You don't even need alternative research. You can find PayPal cheaper than Amex at the time and many other large companies where valuation is driven my charts and sentiment. Its crazy